|

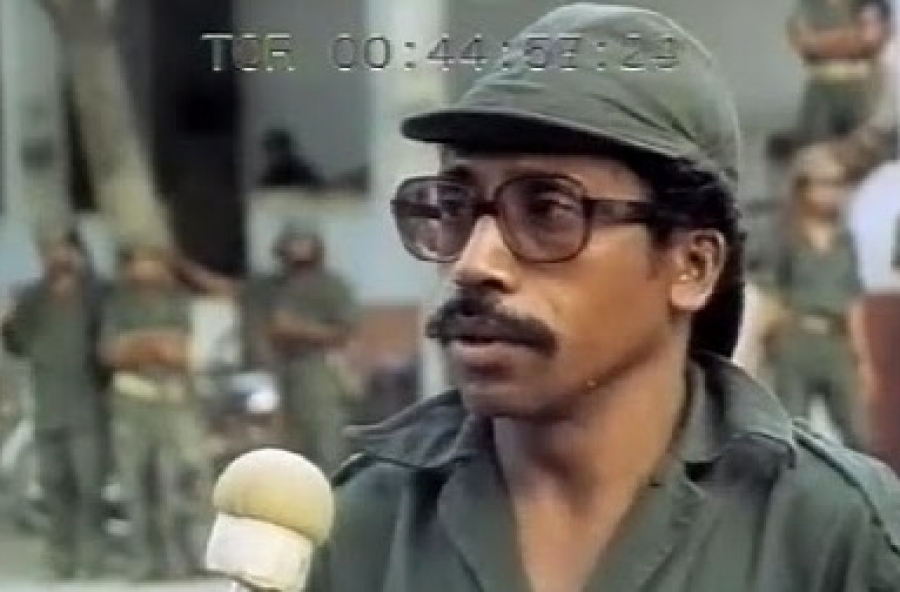

| "Viva Timor Leste....", lian halerik grupo 29 wainhira haksoit tama ba Embaixada USA laran. Hare foto iha oin Antonio Ramos Naikoli kumu-liman ho Luir da Costa kaer hela pamfletu. |

On the morning of Saturday 12 November 1994, a number of East Timorese arrived in taxis outside the US Embassy. They climbed over the 2.6 meter railings and jumped into the embassy compound before security guards positioned outside could stop them. Once inside, they unfurled banners and chanted ‘Free East Timor.’ Dozens of riot police from the Mobile Brigade (Brimob) arrived soon afterwards and surrounded the embassy. A stand-off began in full view of the international media, and the cause of East Timor was dramatically reasserted onto the international agenda.

This was no spontaneous action. It had been planned meticulously, and had its origins more than a year before when seven East Timorese students had entered the Jakarta embassies of Finland and Sweden with the intention of staying there as long as possible. Foreign supporters such as Dr Juan Federer had prepared these students on the procedural details of how to enter the embassies, how to conduct themselves once they had been allowed to enter, how to insist on their rights, and how to resist the pressures to which they would be subjected in order to get them to leave.[1] The external solidarity movement had ensured that Finnish and Swedish media and human rights defenders were briefed about the developing situation. The problem had been that the students – despite their intentions and training – were too frightened by the task and too unfamiliar with the pressure of the situation.

They succumbed to a combination of threats (from the Indonesian police) and guarantees of safe passage (from the Indonesian Foreign ministry, including Francisco Lopes da Cruz). Those in the Finnish embassy left after a day, while those in the Swedish embassy left after 10 days. Several months after their exit, and after considerable harassment by the Indonesian authorities, they were allowed to go to Portugal without much publicity. Embassy staff had been quite unsympathetic to them, and had pressured to leave quickly so as not to upset their countries’ relations with the Suharto regime. The students’ quick exit from the embassies was unhelpful to the independence cause, which required that they stay put for as long as possible in order to create an international incident and focus the world’s attention on East Timor. However, the solidarity movement and the East Timorese students in Indonesia learnt valuable lessons from the experience, and were much more professional at the 1994 APEC summit.

A few leading Renetil activists held a secret meeting in Salatiga to discuss what action to take at the APEC summit. During this secret meeting the Renetil activists realised that they had to make a vital decision – should they jump over the walls of the US embassy or not? There were intense debates about this in Salatiga. Subsequent meetings were held in other cities with the rest of the Renetil group. In the end they decided that ‘we would have to take the risk, sacrifice some of our people, because we cannot lose this moment.’[2] They decided they would not leave Indonesia for asylum in Portugal but stay in the embassy; they wanted to refute Indonesia’s claims that the East Timorese were opportunists who wanted a better life in Europe. Once this consensus had been reached, Aderito de Jesus Soares, a student at Satya Wacana University who was Head of Renetil’s Political Analysis section, went back to Salatiga to convey the news to Dr George Aditjondro and Dr Arief Budiman. He asked them to alert their contacts in Jakarta to be prepared to monitor the situation and react to requests for emergency assistance. Both academics agreed.

A four-phase plan was developed: there would be a concentration phase, a deployment phase, an occupation phase and an exit phase.[3] The operation would be led Carlos da Silva Lopes. In the first phase, ninety East Timorese students from universities in Bali and Java arrived covertly in the East Javanese city of Surabaya. Everyone was careful to keep a low profile so as not to attract the attention of the Indonesian intelligence services. They rehearsed procedures, cover stories, and actions in the event of capture. They made final security checks and took counter-surveillance measures, and then began the deployment phase, leaving for Jakarta in two separate groups on 11 November.

A military intelligence officer arrested one student as soon as they alighted at Jakarta railway station. The others in his group dispersed immediately, but 41 of them were arrested. Of these, 36 were transported to police headquarters in East Java under tight escort. The other five were taken to the Bakorstanas office (Body for the Coordination of National Stability) and subjected to immediate interrogation. The remaining 49 students caught taxis and headed for Merdeka Square, which was adjacent to the US Embassy. They began the occupation phase immediately, climbing over the Embassy fence as soon as they got out of the taxis.[4] One student was arrested in the attempt. He was taken to Gambir District police station in downtown Jakarta and severely beaten. The arrival of more and more police meant that not everyone was able to get into the embassy on the first wave. They escaped arrest by fleeing the scene on foot or jumping into passing buses, and then regrouping. A group of three students then made another attempt to scale the fence. One was successful, one was arrested, and one evaded arrest, escaping once again to a pre-arranged location. Some students did not return to their campuses but made their way to Salatiga to seek shelter with Aderito Soares. Once again, Dr George Aditjondro came to the rescue, providing money to buy food and look after them.

By the time the authorities had cordoned off the embassy and erected barricades, a total of 29 students had entered the embassy compound. One of them, 26-year old Armindo Freitas Fernandes, had suffered lacerations to his neck while scaling the fence. The others made no further attempt to climb the fence but stayed in the vicinity to be of assistance, or travelled to the APEC conference centre three kilometres away and discreetly briefed members of the press corps. The students inside the embassy maintained tight discipline: Domingos Sarmento Alves was the only one who would speak on their behalf. He had a letter addressed to US President Bill Clinton reminding him that 12 November was the third anniversary of the Santa Cruz massacre, and seeking his intervention in support of East Timor. The letter, copies of which were also distributed by external solidarity groups, had been carefully crafted in diplomatic language that was acceptable to the US public and mainstream media. It said that under the Clinton administration, ‘the United States has proven once again to the world its moral responsibility’ with its achievements in ‘the difficult Middle East peace process, in the prevention of a second invasion of Kuwait by Iraq’ and the ‘restoration of democracy in Haiti.’ The letter called for the release of Xanana Gusmao and other East Timorese political prisoners, and an investigation into the Santa Cruz massacre. However, it did not stop at East Timorese issues; it openly made common cause with democratizing forces in Indonesia, calling for ‘the right of Indonesian workers to organize,’ the release of trade union leaders like Mochtar Pakpahan, and the granting of amnesties to ‘elderly and incapacitated Indonesian political prisoners.’[5]

As expected, the students were offered guarantees of safety if they left the embassy. They responded by stating emphatically, ‘We did not come here for guarantees that we could leave the embassy freely. We came to demand the release of Xanana Gusmao.’[6] US embassy staff, keen to make the students leave before the arrival of President Clinton, offered the students secure transport to the nearby Vatican embassy. This offer too was rejected. Embassy staff ensured that the students received as few creature comforts as possible. They were not allowed into the embassy buildings but were confined to a corner of the car park, receiving no protection from the sun, rain and wind. They were given rice and water but nothing else. They used plastic bags to dispose of bodily wastes because they were not permitted to use the embassy toilets. Armindo Freitas Fernandes was able to go to a nearby hospital to receive treatment for his neck injuries under a guarantee of safe passage. Five other students began to complain of fever and stomach pains, with doctors suspecting that they had contracted typhus as a result of their living conditions. The students’ requests to meet President Clinton or Secretary of State Warren Christopher were denied. For their part, the students rejected as inadequate an offer by US Ambassador Robert L. Barry to convey their message to President Clinton.

In the middle of all this, US journalists Allan Nairn and Amy Goodman, who had been present at the Santa Cruz massacre three years before, tried to organize their own press conference at the APEC centre. Indonesian security personnel seized them as they distributed their leaflets. Other journalists immediately rushed to their side, and an hour-long impromptu press conference ensued against the wishes of APEC organizers. Among other things, Nairn and Goodman pointed out that they had just flown to Jakarta after a 20-hour detention following an unsuccessful attempt to re-enter East Timor.

Meanwhile, Indonesian police at the embassy had erected barriers separating the students from watching journalists. Police and military personnel surrounded the embassy, taunting and threatening the students inside. They created enough noise to make sleep impossible for the students. Jakarta’s police chief, Major-General Hindarto, claimed that one of the students was a suspect in a murder, and would have to come out for questioning as part of the police investigation. The students refused, saying that Hindarto’s claim was no more than a ploy to distract attention from Indonesia’s human rights abuses in East Timor.

The students’ elaborate preparations and rehearsals contributed to their strong discipline. They rejected numerous offers of safe passage and asylum, staying inside the embassy for twelve consecutive days. After ensuring that the international media’s focus during APEC was not on Suharto’s success story but on East Timor, the students accepted an offer of asylum to Portugal, thus beginning the fourth phase of their operation. They received new clothes at the embassy and were taken in a Red Cross bus to the airport for their flight to Lisbon. After arriving at Lisbon airport on Friday 25 November, they resisted the temptation to speak triumphantly to the waiting media. Instead, they indicated they would say nothing until a press conference the following Monday, which would be led by Jose Ramos-Horta. Thus they maintained self-control and discipline from the start to the finish of their operation. They had achieved their aim, which was not to seek asylum but to stay in the embassy for as long as possible.

There would be several subsequent embassy occupations in Jakarta. In 1995, five East Timorese entered the British embassy, eight entered the Dutch embassy, 21 entered the Japanese embassy,[7] nine entered the French embassy, and – on 7 December, the twentieth anniversary of the invasion, 112 Indonesian and East Timorese supporters entered the Russian and Dutch embassies. The large number of East Timorese entering foreign embassies led some Portuguese activists to suspect that Indonesia was encouraging asylum attempts in order to remove radical East Timorese activists from Indonesian territory.[8] In 1996, two East Timorese entered the Australian embassy, five entered the New Zealand embassy, 12 entered the Polish embassy and four entered the French embassy. Embassies in Jakarta were practically converted into fortresses to prevent these actions.

The spectacular non-violent action at the APEC summit stole the regime’s thunder, regained the initiative, and gave renewed confidence to Indonesian pro-democracy activists. At the trial of Jose Neves a month after APEC, his Indonesian lawyers from the Legal Aid Foundation made unprecedented statements challenging the legality of the occupation and openly arguing that Neves’ actions (sending faxes about East Timor to foreign groups) were a legitimate form of struggle. George Aditjondro, who appeared as an expert witness for the defence, proudly retold his ‘Ha Ha Ha Ha’ joke before the media and drew sharp parallels between Neves’ actions and the actions of Indonesians studying in Holland during the Dutch colonial period. East Timorese independence campaigners and Indonesian pro-democracy activists would combine to great effect in the 1990s.

[1] Personal communication, 11 December 2008; See also J. Federer, The UN in East Timor. (Darwin: Charles Darwin University Press, 2004). Kirsty Sword, then the Jakarta-based representative of an Australian NGO, also participated in the plan.

[2] Interview with Aderito de Jesus Soares, December 2008.

[3] Except where otherwise indicated, the description of the US embassy occupation is reconstructed from a number of sources including interviews with some participants.

[4] Until the very last minute, not all the students knew that the plan was to jump over the walls of the embassy. Some believed they were simply there to protest and then escape.

[5] All quotes are from the letter, a copy of which is in my possession.

[6] J. Wagstaff, Timorese bed down at Embassy, Reuters, 12 November 1994.

[7] This action was planned to coincide with the start of the APEC summit in Osaka, Japan.

[8] According to people familiar with the East Timorese who went to Portugal, some made use of their stay to study, gain qualifications, and return to a free East Timor. Some settled down in Portugal or other EU countries. Some were victims of trauma and cultural shock, becoming violent trouble-makers, to the displeasure of their Portuguese hosts.

[2] Interview with Aderito de Jesus Soares, December 2008.

[3] Except where otherwise indicated, the description of the US embassy occupation is reconstructed from a number of sources including interviews with some participants.

[4] Until the very last minute, not all the students knew that the plan was to jump over the walls of the embassy. Some believed they were simply there to protest and then escape.

[5] All quotes are from the letter, a copy of which is in my possession.

[6] J. Wagstaff, Timorese bed down at Embassy, Reuters, 12 November 1994.

[7] This action was planned to coincide with the start of the APEC summit in Osaka, Japan.

[8] According to people familiar with the East Timorese who went to Portugal, some made use of their stay to study, gain qualifications, and return to a free East Timor. Some settled down in Portugal or other EU countries. Some were victims of trauma and cultural shock, becoming violent trouble-makers, to the displeasure of their Portuguese hosts.

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário